Your Nose, My Nose

네 코, 내 코

circle 동글이

November 23, 2024

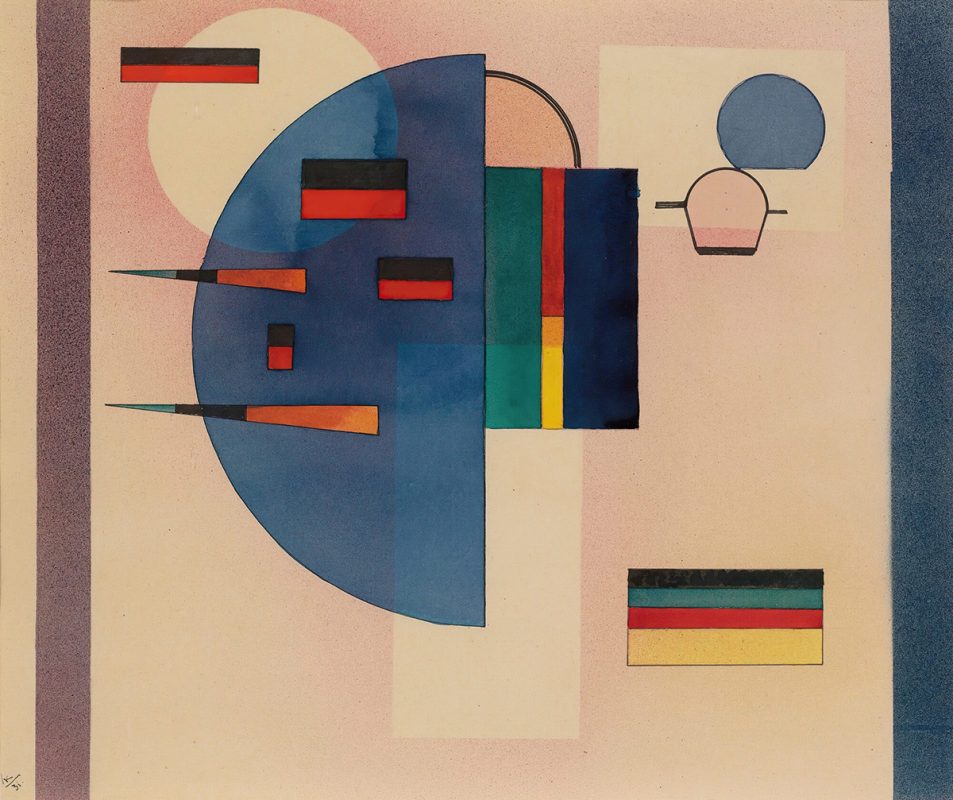

Wassily Kandinsky, Beruhigt(Calmed), 1931

Wassily Kandinsky, Beruhigt(Calmed), 1931

When COVID-19 spread, some people temporarily lost their sense of smell. It was a moment of realization for many—“I should’ve appreciated it while I had it.” The sudden loss of a sense we had always taken for granted was not only confusing but even left us feeling utterly disoriented. With the loss of smell came the loss of taste as well. I remember eating a very spicy bowl of mala soup, feeling the tingling heat on my lips and the spiciness in my mouth, but no flavor whatsoever. This experience made many people newly aware of just how much scent influences our sense of taste.

The process of smelling begins when volatile scent molecules floating in the air enter the nose and are detected by our olfactory system. As we breathe in, these light molecules enter the nasal cavity, where they warm and moisten as they pass through. Along the way, they reach the olfactory epithelium. In the olfactory epithelium, olfactory neurons hang like roots, ready to pick up scent molecules. When these scent molecules reach the olfactory neurons and bind to the olfactory receptors within, the process of smell begins.

The relationship between olfactory receptors and scent molecules is often compared to that of locks and keys. However, the match isn’t a perfect 1:1. There are quite a few “master keys,” meaning that many different scent molecules can open the door to an olfactory receptor. (Of course, unfortunately, some molecules never find their match.) A person typically has about 400 different olfactory receptors, and there are around 400,000 known scent molecules. In theory, the combinations of smells a human can distinguish could amount to over a trillion. Though some research suggests the number is less than 5,000, the general consensus is that humans can identify around 10,000 different scents. However, there’s something even more fascinating than the sheer number of scents: just as every person’s appearance is unique, so are their olfactory receptors. This means that the lock-and-key combinations of scent molecules and olfactory receptors are different for everyone, which suggests that no two people experience the same smell in exactly the same way.

When I blend about two or three different scents and hand them out for people to smell, everyone reacts differently. For example, if I blend lavenderand vetiver and give someone a scent strip, one person might only detect the vetiver, while another might say that the vetiver smells too much like herbal medicine. Yet someone else could find the vetiver’s earthy warmth pleasant. While, broadly speaking, most people perceive scents similarly, it’s not like visual information where everyone processes the same data in the same way. I’m always reminded how deeply personal and mysterious the sense of smell is. The scent that enters my nose is something unique that I cannot fully share with anyone else. Even if we all use the same perfume, no two people in the world will experience the scent exactly the same way, so in a way, everyone ends up having their own personal fragrance. The same applies to the way our sense of smell influences our taste in food. While we may share the experience of enjoying a meal, along with the joy of conversation and company, we are only aligning on similar flavors and sensations, not identical ones. Smelling and tasting, and then using language to express those universal yet deeply personal experiences, is a beautiful way for people to share and find common ground.

코로나19가 퍼질때 냄새를 일시적으로 못 맡는 사람들이 생겼다. ‘있을 때 잘할걸’ 평소에 당연시 여겼던 감각이 사라지니 당황스러움을 넘어 잠시나마 황망하기까지 했다. 후각을 상실하니 동시에 미각도 잃었다. 아주 매운 마라탕을 먹는데 입술이 얼얼하고, 입안에 얼큰한 기운만 느껴질 뿐 아무 맛도 느껴지지 않았다. 이러한 경험을 통해 맛을 좌우하는 데 향이 얼마나 큰 영향을 미치는지 많은 사람이 새삼 깨닫게 되었다.

냄새를 맡는 활동은 공기 중에 부유하는 휘발성의 냄새 분자가 코에 들어오는 것으로 시작해 향기를 읽어내는 것까지의 과정이다. 공기 중에 떠다니는 가벼운 분자는 우리가 숨을 들이마실 때 비강으로 들어온다. 냄새 분자는 점차 따뜻해지고 축축해지면서 비강을 지나고, 그러면 거기 후각상피가 있다. 후각상피 안에 후각 뉴런들이 마치 뿌리를 내린 모양으로 매달려있다. 이 후각 뉴런 안에 있는 후각 수용체와 여기까지 도달한 냄새 분자가 결합하면 냄새가 시작된다.

보통 후각 수용체와 냄새 분자의 관계를 자물쇠와 열쇠에 비유한다. 그런데 이 자물쇠와 열쇠가 1:1로 대응하지는 않는다. ‘만능 열쇠 키’가 꽤 많아서, 상당한 종류의 냄새 분자가 후각 수용체의 문을 열 수 있다. (물론 안타깝게도 끝까지 제 짝을 못 찾는 애들도 있다.) 한 사람이 가진 후각 수용체는 약 400여 개 정도 된다고 하고, 냄새를 가진 분자는 약 40만 종류로 알려져 있다. 인간이 식별할 수 있는 냄새를 경우의 수로 따지면 이론상 무려 1조 가지나 된다는 말이다. 물론 5000 가지에 못 미친다는 연구도 있지만, 보통 식별 가능한 냄새만 추려도 약 1만 가지라는 것이 통설이다. 그런데 냄새의 종류가 엄청나게 많다는 것보다도 더 신기한 사실이 있다. 사람의 생김새가 모두 다르듯 후각 수용체도 서로 다르다는 점이다. 이 말은 열쇠(냄새 분자)-자물쇠(후각 수용체)의 조합이 다 다르다는 말이고, 그렇게 따지면 결국 하늘 아래 똑같은 냄새를 맡는 사람은 존재할 수 없다는 뜻이 된다.

약 3가지 정도의 향을 블렌딩해서 여러 사람에게 맡아보라고 건네면 다들 반응이 다르다. 예를 들어 라벤더, 버가못, 베티버를 블렌딩하여 시향지를 건네면, 어떤 사람은 라벤더와 베티버 향만 인지하기도 하고, 또 다른 사람은 베티버의 한약같은 향이 너무 강하다고 말하기도 하고, 누군가는 베티버 향이 따뜻한 흙냄새 같다고 좋아하기도 한다. 물론 넓게 생각하면 다들 유사하게 향을 인지하는 게 사실이지만, 시각적 정보처럼 모두가 동일한 데이터를 받아들인다고 볼 수는 없다.

향기라는 게 너무나 개인적이고 비밀스러운 감각이라는 점을 항상 곱씹게 된다. 내 코에 들어온 향기는 다른 사람과 공유할 수 없는 유일무이한 것이다. 같은 향수를 사용하더라도 세상에 똑같은 향을 맡는 사람은 없어서, 모두가 자신만의 향수를 갖게 되는 셈이다. 후각이 영향을 미치는 미식도 마찬가지다. 서로 나누는 즐거운 대화와 함께하는 시간, 그리고 적당한 맛의 유사함을 공유하며 좋아하고 있을 뿐이다. 향을 맡고 음식을 먹으면서, 보편적인 감각의 지점을 언어를 사용해 공감하고 나누는 일은 서로의 의견을 공유하고 합의해가는 아름다운 일이다.